|

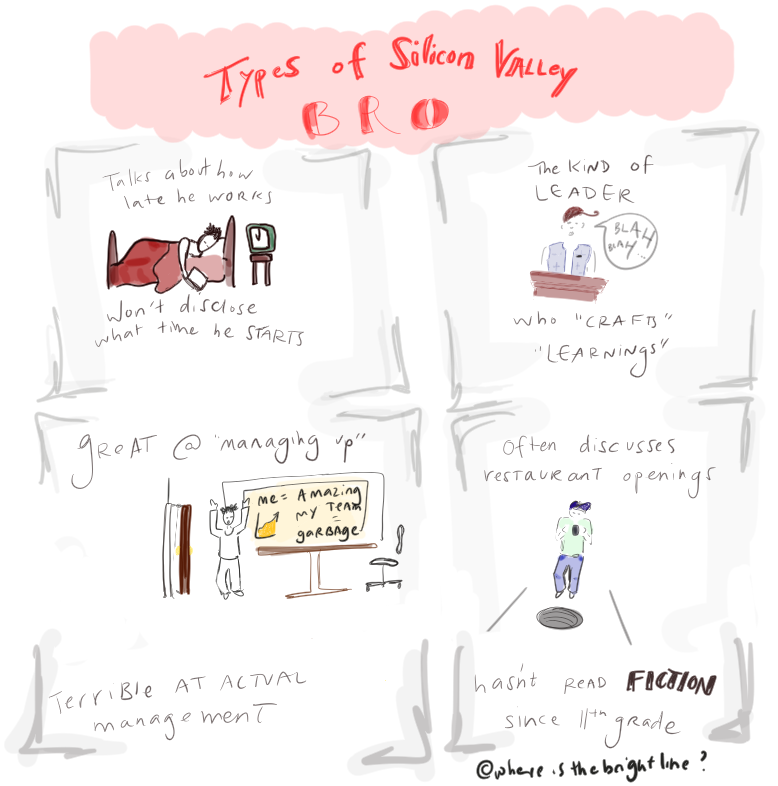

as i've been widening my network in SF over the past year, i've heard a repeat note on my personality: that i don't have enough confidence.

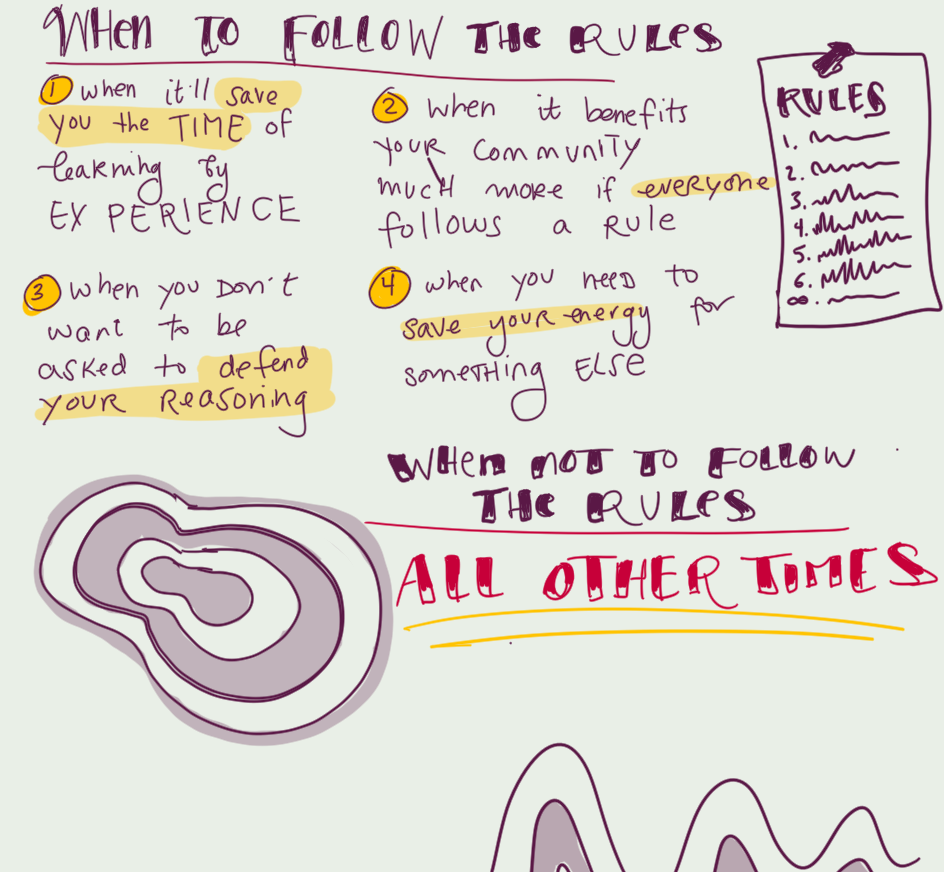

i struggle with this feedback, because, mostly, I get it. professional confidence is a thing. i'm ten years into my career, and i'm not a complete idiot. i've worked at some of those "go-getter" type companies where people describe themselves with words like "thought leader" and "proactive" (don't get me started on 'empathy' and 'assuming good intent'-- that for another day). it's a big part of my work to make people feel assured that i'm completing my work in a professional way. this is what people mean, i think, when they talk about confidence. and i have a lot of methods to make people feel assured. documenting my projects, making my assumptions and my work reproducible and defensible-- these are core aspects of my profession. i understand, in my head and through my experience, that it raises more questions than it answers for a personal to truly "lack confidence" in their professional work. and despite the processes i've learned and developed, i understand that i don't always project that confidence that makes people feel assured. but something about this feedback just doesn't sit right with me. i'm an analyst, and my job is to create frameworks that help guide decisions. it's often extremely "gray area" subjective work that needs to be defensible, as if it were objective. so my 'bottom line' is often, "Can we make a decision based on this information?" Being able to get an analysis to the realm of directing practical decisionmaking is really important. "good enough to make the next decision" is often the goal of my work. i've been thinking about how useful rules can be. following recipes, dress codes, behavioral guidelines, traffic laws. great things that make life easier. but when does it make sense to break rules, or ignore them?

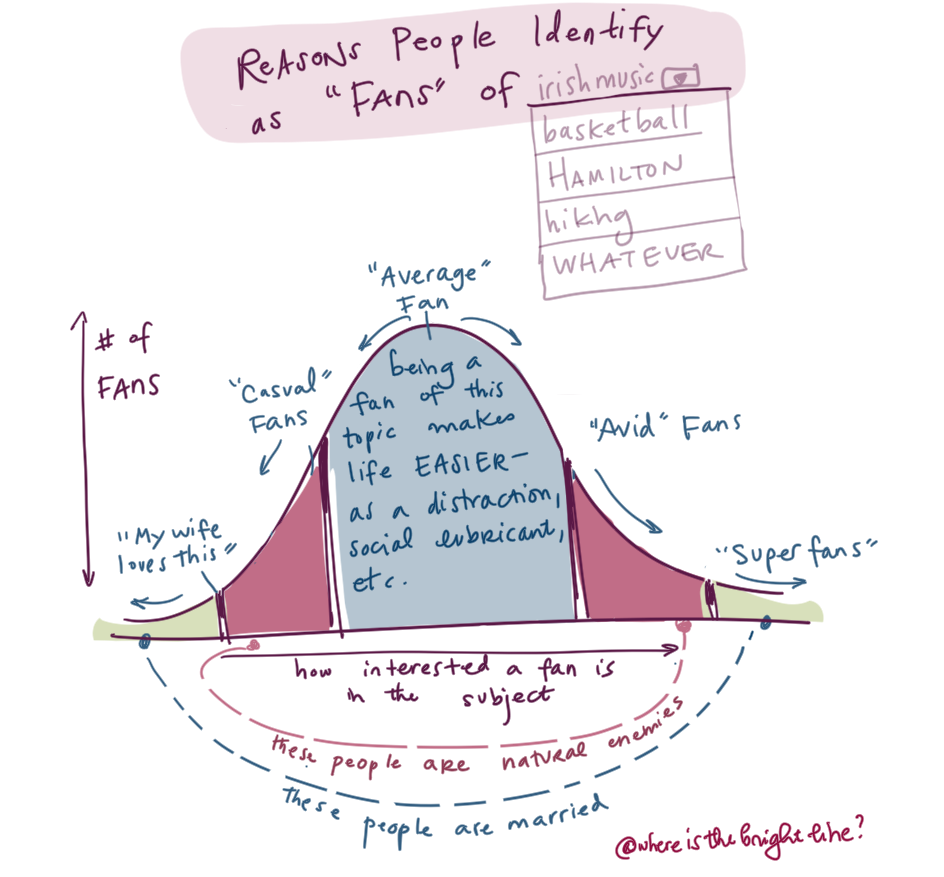

i heard a female standup comedian once do a bit about standup fans who like to sleep with standup comedians. she referred to these types of people as 'chucklefuckers.' apparently it's a thing, like, maybe a fetish? or a, um, niche? i don't know. i didn't do any research on this. it made me feel so uncomfortable, like there's something fetishistic about being interested in a person with a great sense of humor. but i got the feeling towards the end that the term was meant to demonstrate the similarities between touring the country as a standup comedian and touring as a rock musician. that the intense loneliness of being on the road might be met with some kind of intimacy, but that a traveling comedian shouldn't take it too seriously, because it's more likely to be with folks who are interested in celebrity.

her bit got me thinking: dating a comedian must be really weird. a weird balance, specifically. on the one hand, if you're dating a comedian, you really see them up close, and a lot MORE. so much of standup comedy is well planned, distilled, with the perspective highly controlled. if you follow a comedian home and live in their house, you lose a lot of those parameters. i imagine that you'd see all their offstage, not-really-very-funny moments. you see the lead-up, the input-- and you lose the lighting, the forethought, the social cues, and the audience. so, inevitably, you must see a less-funny version of that person. and that, if only because they're not scripted and practiced-- they're really just out there, experiencing life with you. and life doesn't often happen the way the stories end up coming out on stage. i would expect that the more time you spend with a standup comedian, the harder it is to laugh at their jokes, because you 'get' where they came from better. i also imagine that you, being present for some of the source material, remember those things as being less funny, because you're not that fucking funny and you remember it with your not-funny brain and it feels like something important has been erased. but on the other hand, if you're dating a comedian, you must see this person up close. like, when they ARE being funny in their everyday personal lives. so you all of a sudden have to go from thinking "he was medium funny in his netflix special, there were notes i had" to "here he is at the grocery store making an offhand joke about avocados, and yes, he is way funnier than i am." that direct comparison must be a strange experience. I heard an amazing suggestion once for the Olympics-- that in any competition, there be a "average Joe" competitor alongside the Olympic competitors, to demonstrate just the superhuman speed and strength of athletes at the Olympics. I love this idea so much. i'm not an athlete-- i'm maybe the antithesis of an athlete, if that's a thing. but if i were dating a comedian, i feel like i'd also have a lot of those moments of feeling very average. i'd be the guy at the olympics, 3 laps behind everyone else, demonstrating to anyone watching how funny my partner is. my life would become a cornucopia of realizations that no, i don't really have standing to critique this person's material. i imagine that as time went on, my personal understanding of how funny this person is would increase, as i keep comparing him to myself. questions i wish i always asked myself when someone's trying to get me to do what they want by showing aggression and anger.

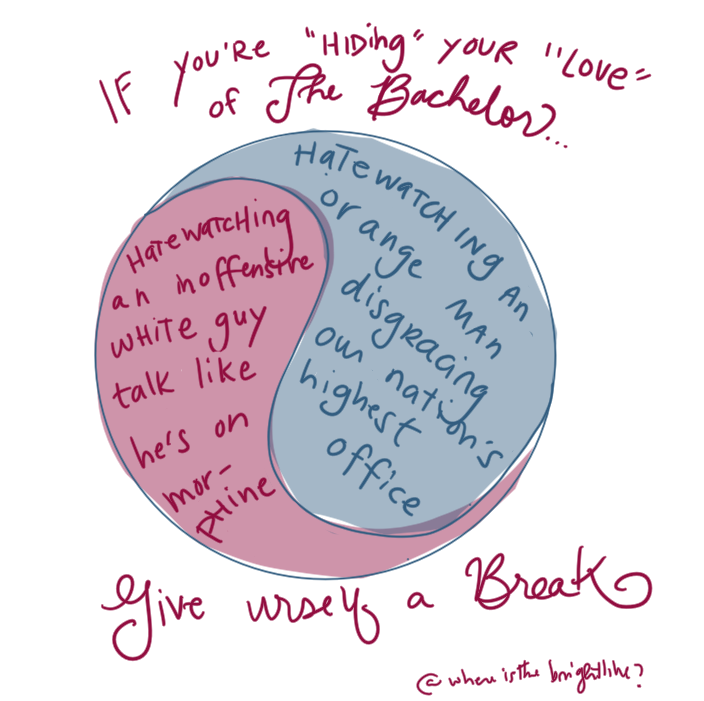

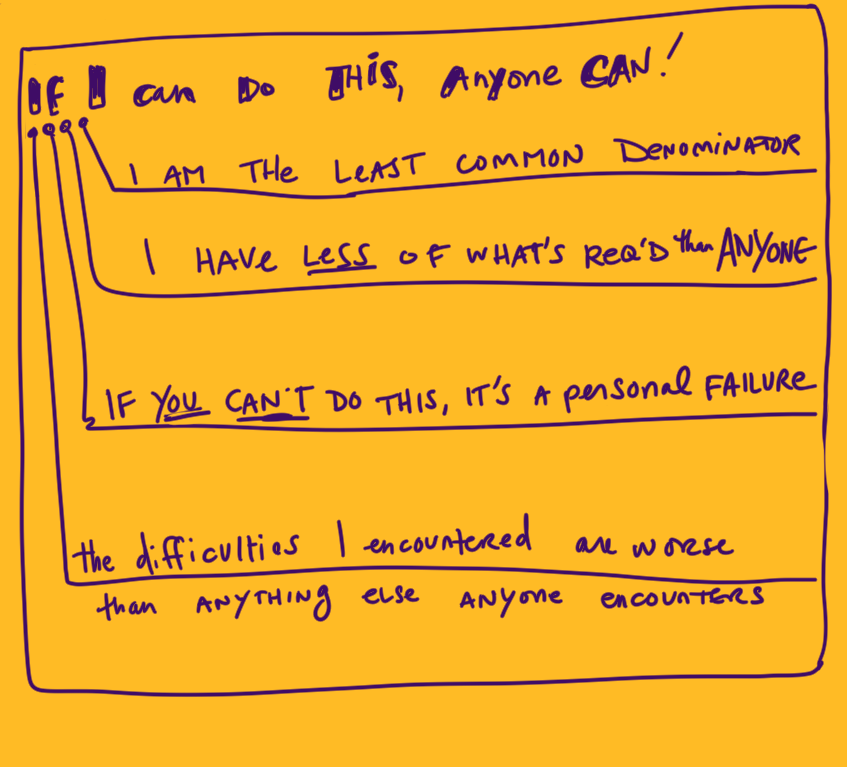

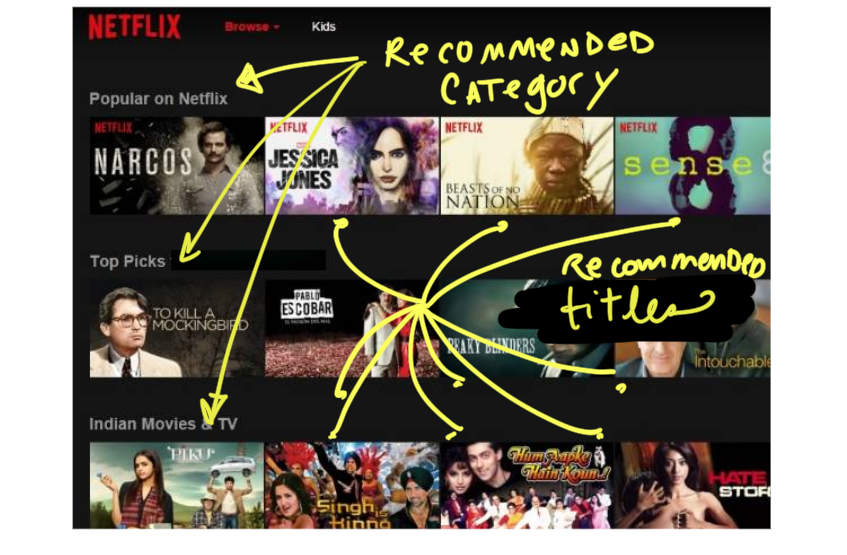

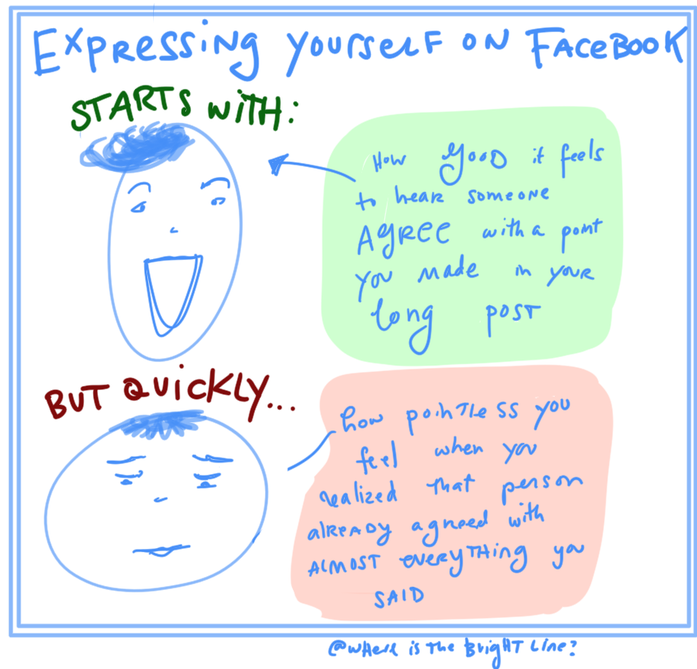

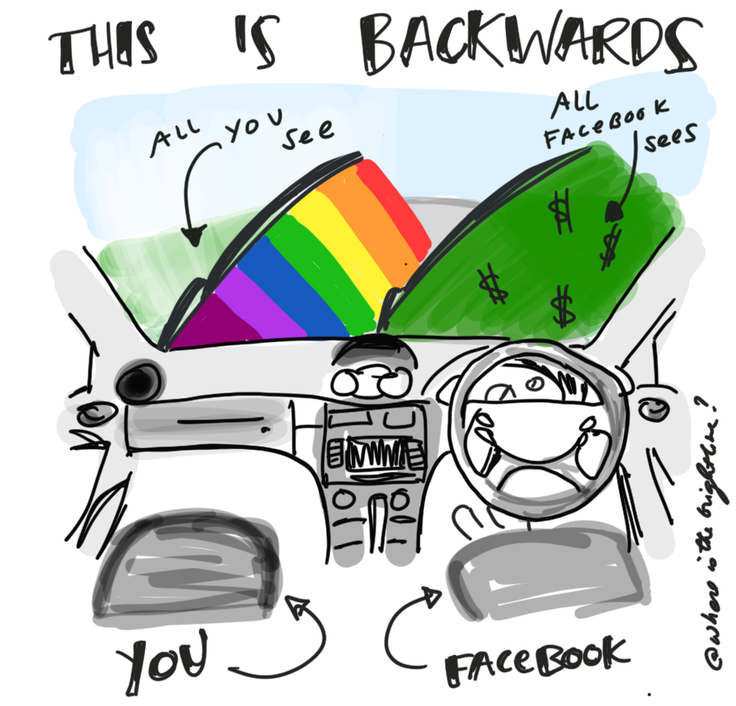

also, what i hear when people say "If I can do this, anyone can!" -- which i hear all the time on reality TV shows for some reason. topic (really, a question): here's an honest question i've been stumbling over for 4 months: what do we get out of content recommenders? what's the benefit to us, as users? i'm not asking about whether they help us discover new stuff, products, content. i know they do that. and i certainly understand the product implication of a good content recommender for a company. they're built to increase loyalty, engagement, to decrease churn, to sell more products, to sell better products. they're built to ensure a better immediate-term outcome. but what i wonder is: how are they better than the alternatives? in an alternate universe, could something better be out there? pre-discussion: what is a content recommender, and how does a basic one work? here's a recommender that a lot of us are familiar with, and an example i'm going to keep referring to. it's netflix! below, i highlight the recommender's output-- Named & Recommended Categories, and Recommended Titles: ok, and... how do recommenders work? recommenders can work LOTS of ways-- so many-- maybe even as many ways as there are engineers. but the bare bones that the recommenders Netflix builds, for instance, start with a list of users, a list of films, and then does some extrapolations predicting ratings of unseen movies based on seen movies and similar users. Visually, a little dataset might look like this: trying to get people to like my page on facebook in the past month: and here's my rumination on why this is happening, because i am so confused by what 'normal' is on facebook, i'm frustrated that not only am i not in the driver's seat, but also can't even see any of the measurement instruments. and lastly because i honestly don't believe that my social network is actually resistant to helping me discover and develop my voice:

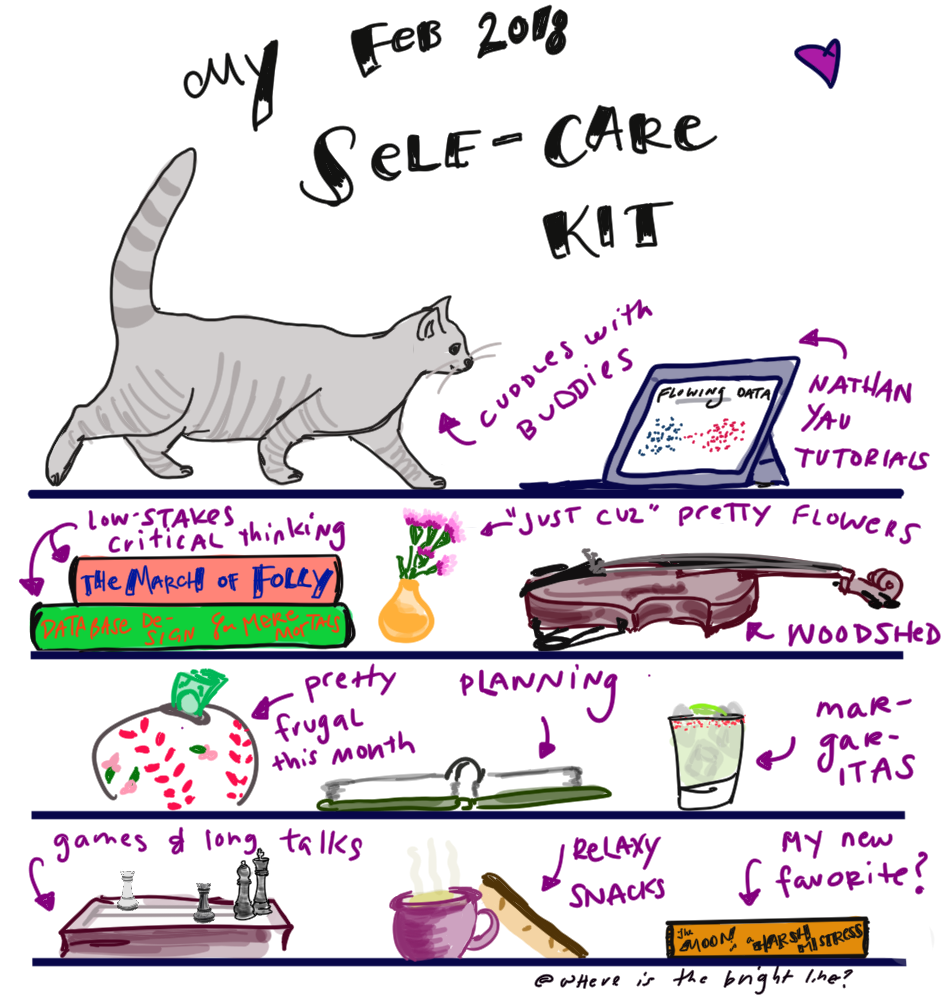

i woke up with this ill-formed idea in my head about emotional norms and baselines, and i keep seeing stories like this one in the NYT on teaching self-compassion to teenagers. chris hardwick on ID10T has been talking about a similar idea-- when do we get to relax, and be done beating up on ourselves? at what level of success do you finally feel like "This is it"? his conclusion: "There is no finish line!" but that doesn't work for me, and that definitely doesn't work for right now. americans are under so much strain. establishing norms and context and baselines is so important in a time when propaganda, misinformation, and disinformation run rampant.

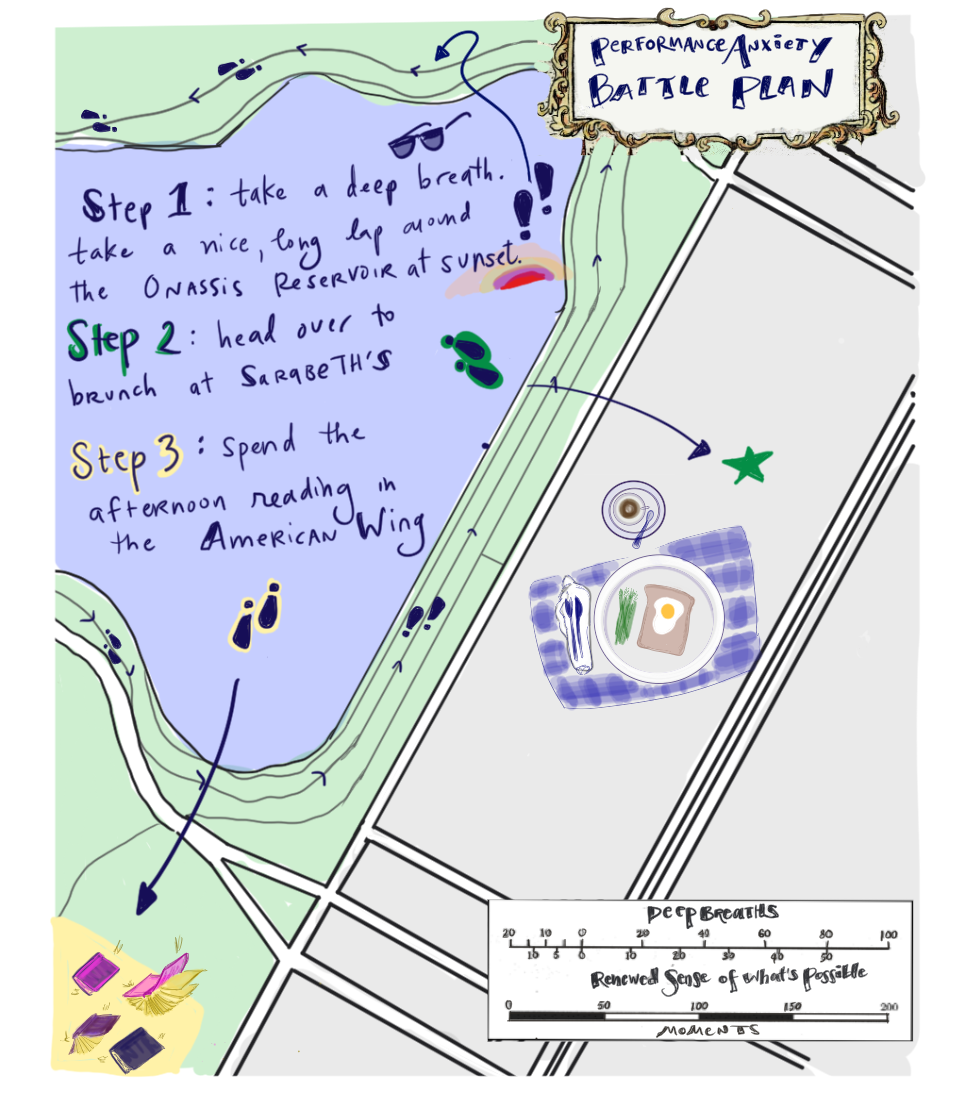

since i started this blog to discuss "what is normal" and "how do we know what we know" it seems like a good time for a somewhat drawn-out stream of thoughts. i'm basically just talking myself tired, here, and i don't come to any conclusions, so just stop reading once you get bored. here goes. for some reason when i feel performance anxiety, sometimes it helps me to mentally picture a couple of really happy memories from the upper east side. i pretend i'm suspended in the world's longest afternoon, free to stay as long as i please. i recommend it highly.

A lovely friend of mine confided in me the other day that they, at 32, were still experiencing fear of rejection. "Fear of rejection." It's funny to me how evocative that phrase is.

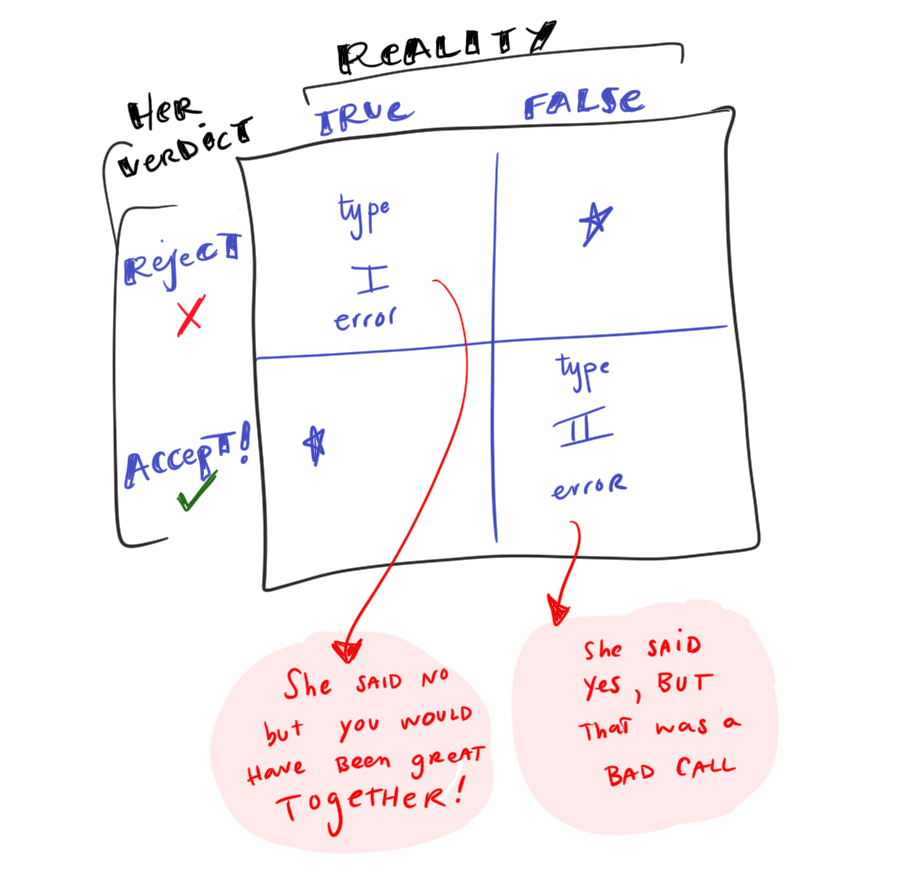

When we hear the phrase "Fear of Rejection," most of us immediately think of same thing. We think of the specific fear of the specific rejection of 1) Asking someone out and 2) Hearing them say no. To me, Fear of Rejection is really vague terminology-- but The Fear and The Rejection are so common that we all know what we mean when we say that. No part of someone talking about Fear of Rejection wonders if maybe the other person is referring to the anxiety a statistician feels that they might erroneously reject a null hypothesis when the hypothesis is actually true. Wait, Null Hypothesis-- we were just talking about dating. Don't jerk me around, Wang OK, well, hear me out-- in a way, Fear of Rejection in a romantic setting is a lot like the fear a statistician might feel about rejecting a null hypothesis when it is true in reality. Here's what I mean by that-- here's a typical Type I vs Type II matrix, with the implication of someone you're asking out making one of those errors: |

Archives

March 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed