|

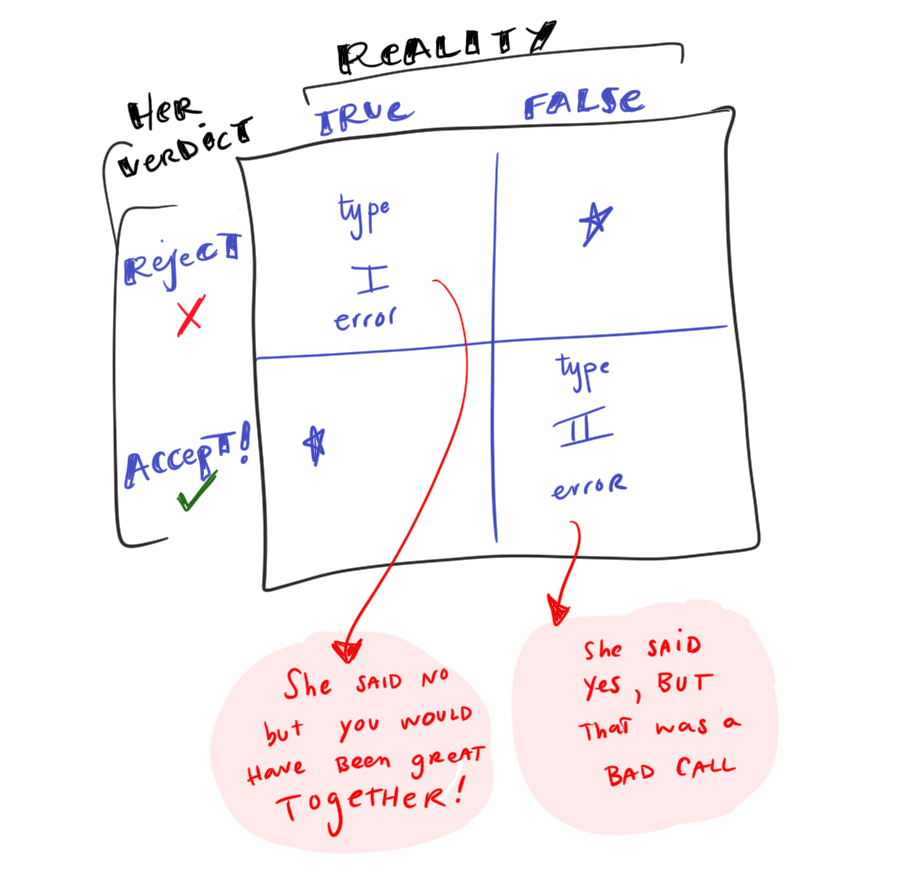

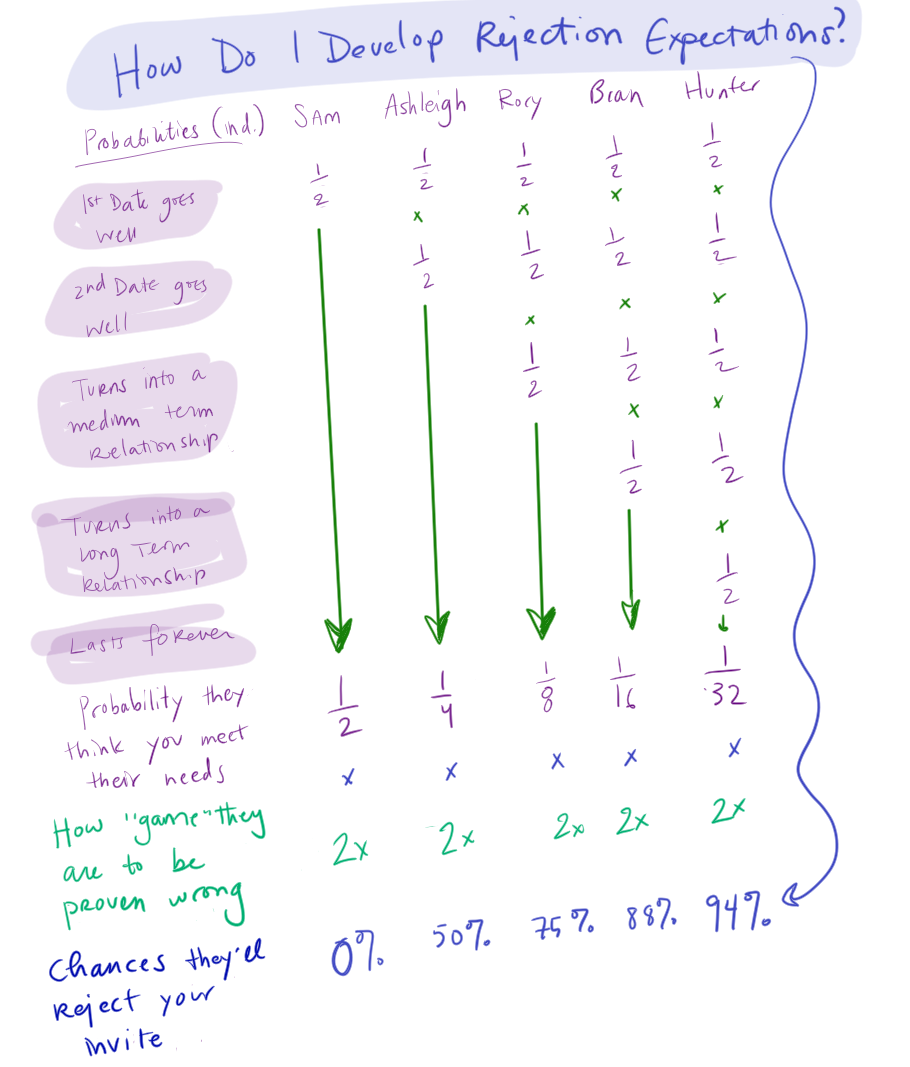

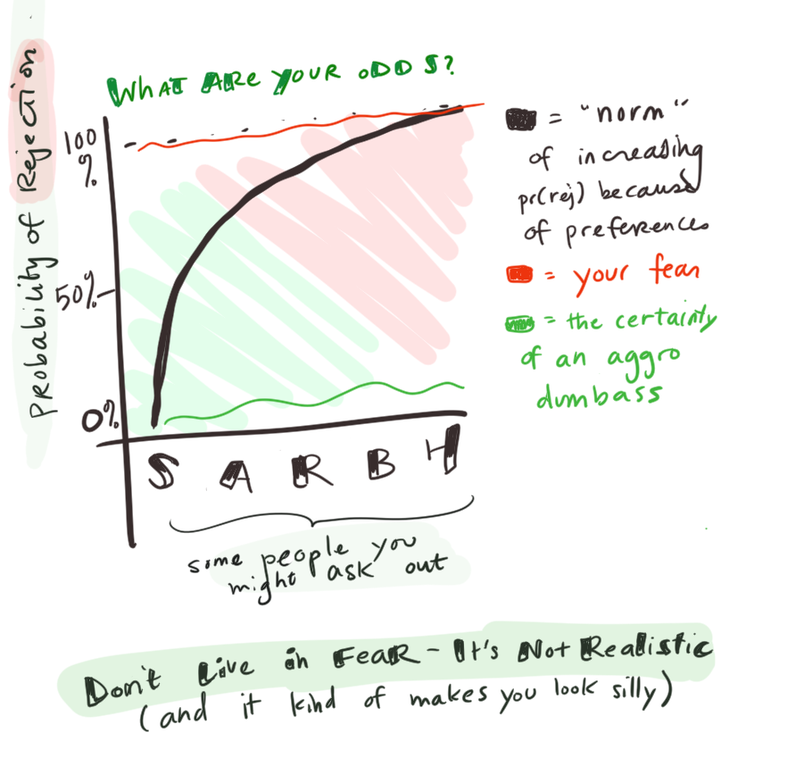

A lovely friend of mine confided in me the other day that they, at 32, were still experiencing fear of rejection. "Fear of rejection." It's funny to me how evocative that phrase is. When we hear the phrase "Fear of Rejection," most of us immediately think of same thing. We think of the specific fear of the specific rejection of 1) Asking someone out and 2) Hearing them say no. To me, Fear of Rejection is really vague terminology-- but The Fear and The Rejection are so common that we all know what we mean when we say that. No part of someone talking about Fear of Rejection wonders if maybe the other person is referring to the anxiety a statistician feels that they might erroneously reject a null hypothesis when the hypothesis is actually true. Wait, Null Hypothesis-- we were just talking about dating. Don't jerk me around, Wang OK, well, hear me out-- in a way, Fear of Rejection in a romantic setting is a lot like the fear a statistician might feel about rejecting a null hypothesis when it is true in reality. Here's what I mean by that-- here's a typical Type I vs Type II matrix, with the implication of someone you're asking out making one of those errors: The above diagram (sorry, I love a diagram though) explains how someone building a predictive model might evaluate the risk of getting it wrong. If I'm developing a test for an illness, or a set of alerts in a nuclear facility, I need to know how 'sensitive' those things will be. If the tests I design are wrong more often than they're right, and the error is a Type I error, that's scary and dangerous. If I tell you you don't have Ebola, and you do-- or if I tell you I'll let you know if Chernobyl is melting down, and I don't-- terrible things can happen. Conversely, Type II errors are pretty bad in those scenarios. If I tell you a million things are going wrong, and none are actually that critical, then my alarm system has failed, too. (If you want to read more about those pesky error types, you can do that here.) I'm not an expert, or really even casually acquainted with knowledge about how most relationships work (I'm a pretty big fan of my own, but I seem to govern by rules that are as similar to other people's rules as video game physics are similar to Newtonian ones), But if I had a gun to my head, I'd guess MOST people are more afraid of a Type 1 dating error than a Type 2. Type 2, for starters, will get sussed out during the first or second date a lot of the time. We don't just accept a person once and then that's it, we're married now. We continue to go through acceptance/rejection phases. So for relationships, Type 1 is a scarier prospect-- it represents the end of possibility, the end of future rejections or acceptances. That makes sense, a bit, to me. Type 1 Errors and Recovering from Trauma One thing that I know, as a human, is that fears are often the result of traumatic events that condition a person to feel fear in similar situations in the future. If you are ever struck by a car while crossing a crosswalk, it's really hard to unlearn the fear you'll feel next time you're around a car or a crosswalk. Olympic athletes are masters of overcoming trauma -- and they have a bunch of tools for doing it. One tool some Olympians use that really blows my mind is watching a video of their accident after it occurs. It must be so hard to watch yourself on video breaking something or injuring something. That's damn brave. Olympic athletes are partly so notable not only because of the enormous amount of work they do in pursuing new levels of competitive performance, but also because of the risks that they take. Yes, their careers are risky, because they might win or lose, but the risk I am thinking about is the risk of catastrophic, life-altering injury. Especially winter sports and gymnastics-- the frequency of injury, and the requirement that you be able to minimize the chances that injury will take you out of the running, are astonishing, I have read so many times that some Olympic athletes seem to be fearless. That word, "fearless," is interesting to me. A fearless person, I think, can't survive very long. Bad things exist and real danger exists. To call a living adult Fearless is weird to me-- it would imply that they're also incredibly, unbelievably lucky and haven't been in a situation where feeling fear kept them alive. That kind of luck might be the way bigger headline for the Fearless person, frankly, Anyway. To me, an Olympian is much less a person born without fear and much more a shrewd statistician who understands what the risks of injury are and how to minimize them-- or at the least, keep from exacerbating the risk of future injury by never 'recovering' mentally from past injuries. Watching a video of your injury immediately after it happens is one way to minimize the risk of letting trauma interfere with future performance. Being explicitly aware of the risks of injuries to high-performing athletes is another. A culture of referring back to the explicit expectations of injury, and recovery rates-- those are powerful tools for Olympians. Suffice it to say, I think Olympian athletes have what's actually a pretty decent idea of how likely they are to be hurt, how likely they are to recover, and whether they should go ahead at full-speed anyway. Olympian Mindsets at a Cocktail Party For a dude at a cocktail party who's scared of asking out the next lady because the last one said no, do the same rules apply as might to the Olympian looking downhill at the first slalom they're attempting after the last run broke their spine? When I hear friends talk about being afraid of rejection, I always wonder what their norms are. Do they expect everyone to say yes, every time? Do they consider themselves SO charming and irresistible that absolutely anyone would say yes to a first date? Or only 90% of people they'd ask out? Or only 50%? How much do our mental models (the way we calculate, intuitively, the likelihood of rejection) take the needs of the other person, rather than just our own need to be accepted, into account? I was doodling with this idea this morning and decided to draw the dumbest possible mental model to help me build my own sense of norms and what the odds of rejection are for a few people who all have essentially the same assessment of the person asking them out, but slightly different criteria for accepting/rejecting a date invite. In the above example, some people-- Sam, Ashleigh, Rory, Bran, and Hunter (yes, these names are the only semi-neutral ones I could think of, I'm aware of how white they sound)-- all basically have the same exact expectations of how a first date would go wit the person who might ask them out. The only difference between any of them is what they're looking for from a potential relationship. The model gives even odds to everyone at every step, and the ONLY variable is the person's preference for a TYPE of relationship. The chances of Sam rejecting your date invite is 0%. The chance that Hunter will is 94%. The incline is super step, even with identical odds and risk profiles. I don't have much to say beyond this example, because our models of preferences and risk tolerance are incredibly complex and we're reevaluating them all the time. They suffer (benefit?) from two-way causality and we do all sorts of little game-theory strategies with each other to try to maximize the odds that we won't be left alone (Why is that, anyway?). I'm no dummy, but I'm finding myself completely unable to know where to begin to map out any of these dynamics. They're intensely complex, interact with each other, and change suddenly. Developing expectations for someone rejecting you or not seems almost pointless on a case-by-case basis. But we somehow take it seriously and personally when we're rejected in the individual case. Even though we can't begin to explain why it's a loss. Please bring it together, Wang-- I'm not getting your point OK OK-- here's my point. If you don't know the norms for Type I errors, you don't know the individual preferences of the person you're asking out, or whether you can have ANY influence over those systems of preference. If you don't know all these things, how can you tell whether a person's rejection of you is a Type I error, or not? And if it isn't an error, how can you tell if the error is because of any particular reason that might affect the next situation you're in? So if you are trying to know how afraid of fearing the next rejection you should be, how are you determining what type the last rejection was? All I'm trying to say is, don't be a dumbass about feeling fear. There's nothing wrong with feeling fear at all, especially if someone rejected you-- or worse, rejected you painfully. My point is, find some context for your pain-- or else you're no better than the "I'm just playing the numbers" troll whose preferences are merely to gain acceptance over rejection, and not a genuine romantic interest.

Good luck out there.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed